The city of Korçë

Are you also going to Albania this summer? Then you will probably travel on to Shkodra, Berat or Gjirokastra after a day in Tirana. There is a big chance that Korça is not on your list, because it is located in the southeast of the country and definitely not on the route to the beaches of the Ionian coast… Too bad! Then you will miss a beautiful and characteristic Albanian city.

I’m going to Korça again this summer for a few days. I love walking along the tree-lined boulevard St Gjergj, right through the city, visit one of the many museums and look forward to eating in the evening in yet another new restaurant in the old villas on the outskirts.

Korça is different from Ottoman cities like Berat and Gjirokastra. It is not a Muslim city, more Orthodox Albanians live there. Korça has a specific atmosphere of its own, with trees, parks and flowers, and everywhere a view of the high mountains. Korça is an old city, with an interesting cultural history, the Albanian Renaissance started there and it is the cradle of the Albanian language and Albanian education. I love the many beautiful old villas with their flower gardens and certainly compared to the capital Tirana there are many low-rise buildings.

Korça also has some very good museums, housed in original residential buildings: the photography museum of Gjon Mili in a striking yellow building, an educational museum, a museum for the landscape painter Vangjush Mio. For other museums, new buildings have been specially built: for the curious Bratko collection and the new museum of Medieval Art.

And then there are the wonderful excursions you can make within an hour’s drive from Korça: to the abandoned and once great Christian city of Voskopoja, Lake Prespa, archaeological excavations…

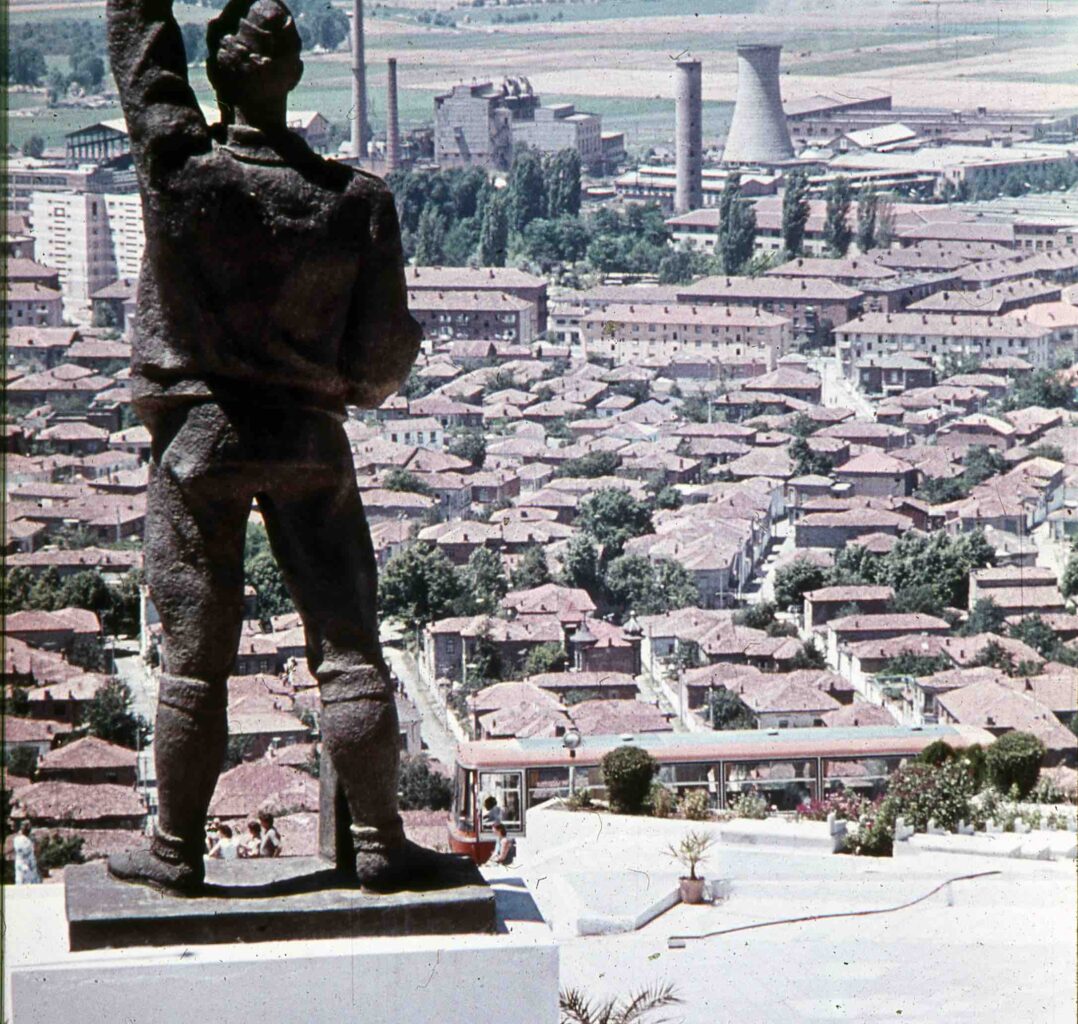

I visited Korça regularly with groups of Dutch people during communism. After arriving at the Albturist hotel Illyria on the square we immediately left by bus to a hill above the city where an impressive statue of a partisan fighter in Albanian costume stood between graves of fighters and war victims.

From there you had a magnificent view of the entire city, the red roofs, the houses and in the distance factories with smoking chimneys. After one of those visits a cheeky one from the group asked if we could walk back to the hotel. That was an unusual request, groups of tourists always had to travel by bus. The guide allowed it (!) and during the descent we suddenly ended up at a real Albanian wedding. In my photo album from 1985 there is a series of photos of a radiant – dressed in white – Albanian bride, who invited us to her wedding party and with whom we danced in a shady courtyard…

We then always went to the Museum of Medieval Art which was housed in a church closed to religion because religion had been abolished in 1967. And the three-day excursion to Korça ended with a visit to a carpet factory and an agricultural cooperative in the countryside. We never got to just stroll through the city. If you got up early – before breakfast – you could go to the old Bazaar near the hotel, which was incredibly poorly maintained. There was no market, no colour, residents did their shopping in state shops.

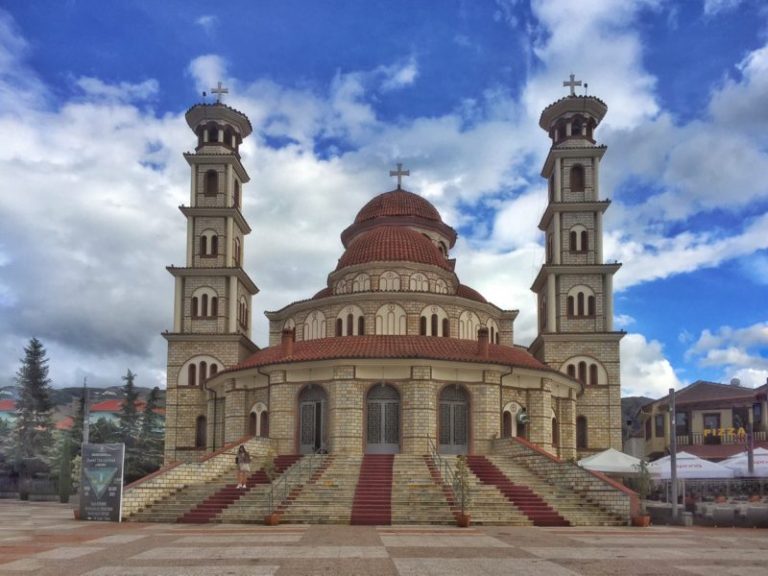

How different Korça was sixteen years later! In 2011 I was back, twenty years after the revolution, together with a friend who had also been to Korça before. The Illyria State Hotel was closed and we took a room in one of the new private hotels. It was strange to see the city again after so many years. No more tightly directed visits. We wandered through the cluttered and crowded Ottoman bazaar, bought antique coffee grinders in a caravanserai and sat on a terrace next to the Korça beer factory. We were allowed to visit all the churches and mosques we wanted: they were all open again. At the end of the boulevard was a huge Orthodox cathedral that was not there when we visited in the eighties.

When I returned to Korça in January 2020, the city had undergone a metamorphosis. The city had been beautifully and daringly renovated. Australian architect Peter Wilson of the architectural firm Bollis + Wilson, after consultation with the then mayor, Niko Peleshi, had carried out a complete reconstruction of the city centre of Korça between 2014-2020, creatively reworking streets and squares, and building a new theatre, museums, lookout tower and town hall. Not everyone in Korça was enthusiastic about his striking interventions. More about that in a next blog!

Below I list ten of my favorite places in Korça. I have many more, all of which will be covered in a series of blogs about Korça.

1. The Martyrs’ Cemetery

A brisk walk takes you to the statue of the ‘warrior in national costume’ high above the town. The statue is central to the cemetery for the fallen of the Second World War (the graves are arranged in the shape of a double-headed eagle, the national symbol of Albania). Standing on the steps of the cemetery you can see the whole town of Korça with its typical white houses with red roofs and walled courtyards.

2. Gjon Mili Photography Museum

In ’the Romanian house’ lived Gjon Mili, born in Korça in 1904 as the son of Vasil Mili and Viktori Cekani, in the then Manastir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. Mili spent his youth in Romania, attended the Gheorghe Lazăr National College in Bucharest and emigrated to the United States in 1923. In 1939 he began working as a photographer for the photo magazine Life (until his death in 1984). His assignments took him to the Riviera (Picasso); to Israel (Adolf Eichmann in captivity); Florence, Athens, Dublin, Berlin, Venice, Rome and to Hollywood to photograph celebrities and artists, sporting events, concerts, sculptures and architecture.

Gjon Mili was a pioneer in the use of stroboscopic instruments to capture a sequence of actions in a single photograph. Trained as an engineer and self-taught in photography, he was one of the first to use electronic flash and strobe lighting to create photographs of more than scientific interest. Many of his images showed the intricacy and flow of movement too rapid or complex to be seen with the naked eye. In the mid-1940s he was an assistant to the famous American photographer Edward Weston.

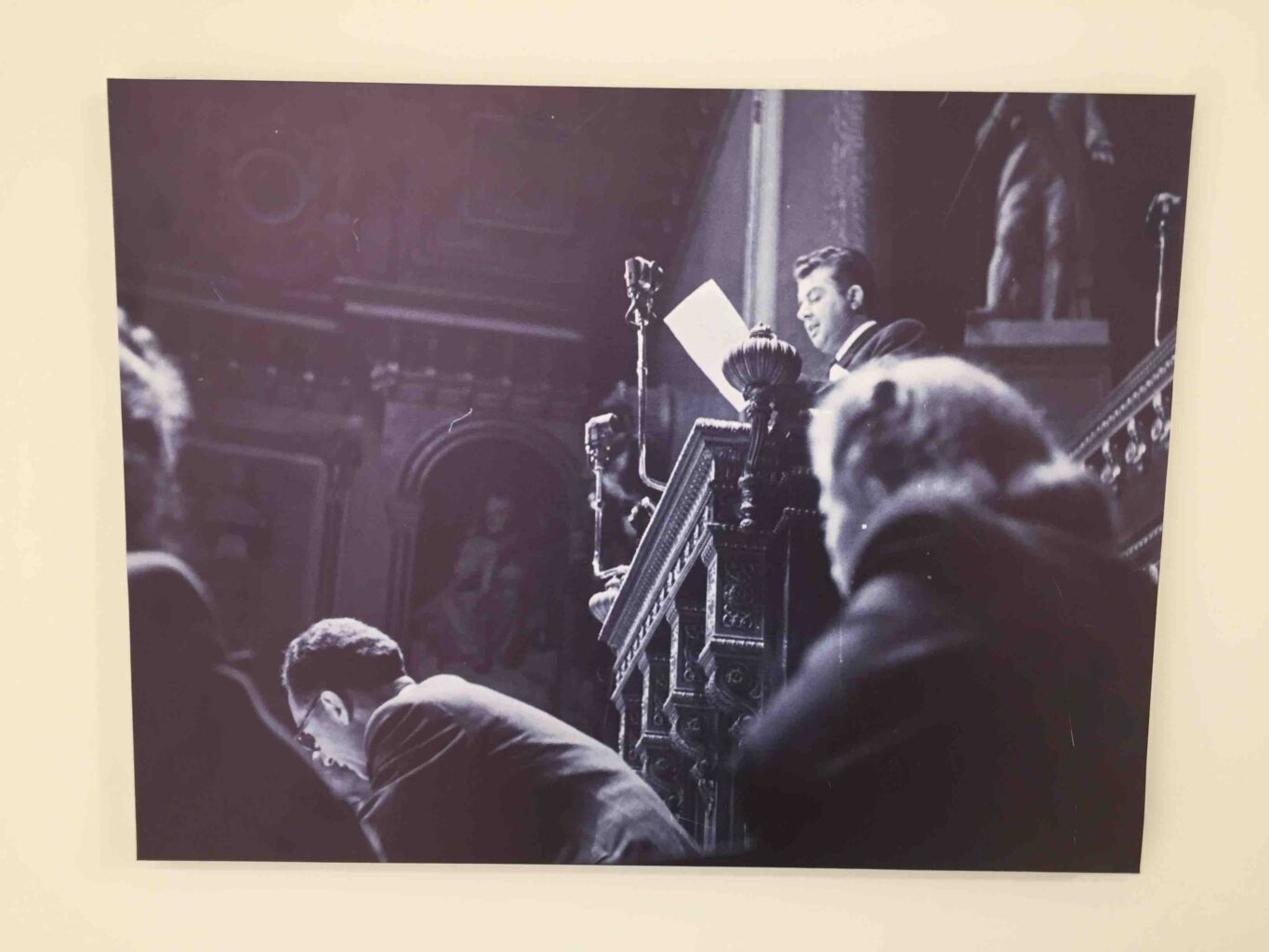

Over the course of more than four decades, thousands of his photographs were published by Life and other publications. The Gjon Mili Photography Museum displays a vast collection of his most iconic photographs alongside moving family portraits and letters from the artist. He was eager to visit Albania after the war but was denied permission by Enver Hoxha. Remarkably, Gjon Mili did take a photo of Enver Hoxha during a speech at the Paris Peace Conference in 1946.

3. The old Ottoman Bazaar of Korça (Pazar I Vjetër)

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Korça’s Ottoman bazaar was enormous. It housed over 1,000 shops and inns, such as the Hani i Elbasanit. Korça quickly became an important stopping place on caravan routes; at one time there were as many as 16 inns (han’s) in the city. In the 19th century, Korça became a particularly prosperous city.

During my visits to Korça in the communist period I always used to sneak out of the state hotel to go to the terribly dilapidated square with the shops. I was very afraid that the bazaar would be demolished, as happened in Tirana. In one of my travel books from that time I write: “To the west of the Albturist hotel, behind the bus station, there is an old, dilapidated neighbourhood around a square, with dilapidated wooden houses and a dingy little hotel. A relatively large number of Roma live in this old neighbourhood. On the street people still weave baskets, trade in herbs and other things. People on the street sometimes play cards and argue more violently than is usual in Albania. The atmosphere is different and much more authentic than in the rest of the city. That is perhaps also the reason why this neighbourhood is regularly used for feature films. The neighbourhood has workshops such as a bookbinding workshop, a blacksmith’s shop, a knitting workshop and a mill where people have their coffee or grain ground. Many men walk around with horse and cart. Every time I notice that part of this dilapidated neighbourhood has been razed to the ground. Here too, blocks of new flats will soon have risen”.

Luckily I was wrong and this didn’t happen.

The Ottoman Bazaar was completely renovated in 2015 with US funding and is a fine example of an old bazaar turned into a lively public space. The market function was relocated. Korça’s restored bazaar has a central cobbled square surrounded by small cafes and tavernas. In the late afternoon, families and groups of friends come for coffee. There are a few very nice cafes, including a branch of Tirana’s famous Komiteti Kafe Muzeum. Around the central square, narrow streets lead to small boutiques, galleries and antique shops. When I’m in Korça now, I go there for a traditional Albanian breakfast of trahana and salep . The original old Elbasan inn, which was still under renovation in 2011, is now a luxury hotel that you can book on booking.com.

4. The Orthodox ‘Resurrection of Christ’ Cathedral

There was once an original old Orthodox St. George Church in Korça. It was dynamited in 1968 on the orders of the communist party. Until 1990, Orthodox believers were not allowed to practice their faith or hold church services.

The new Cathedral of the ‘Resurrection of Christ’ ( Katedralja Ortodokse Ringjallja e Krishtit ) is located at the end of Boulevard Shen Gjergj. It is truly in the heart of the city and is the landmark of Korça. Greece financed the reconstruction of the church (together with Romanian and Aromanian benefactors). Construction of this Orthodox church began immediately after the revolution and was officially consecrated in 1994. The design and warm earth colours are reminiscent of old Byzantine-Greek churches. Inside, the cathedral is decorated in a rather minimalist style with mosaics and carved wooden lamps. It resembles the cathedral of the same name in Tirana. Both are among the largest Orthodox cathedrals in Albania.

5. The Mirahora Mosque

All the photos I took before 1990 show the oldest mosque in Korça, the 15th century Iliaz Bej Mirahorit Mosque. I was fascinated by this precious cultural heritage, which was then in such poor condition.

The Ottoman occupation of Korça and its surroundings began in 1440. Iljaz Hoxha, an Albanian and Christian landowner in the service of the Sultan, who played a heroic role in the siege of Constantinople, was given the honorary title of ‘Iljaz Mirahor’ by the Sultan in 1453. Iljaz Hoxha began developing the city of Korça under the command of Sultan Mehmet II, hence the name Mirahor Mosque. The mosque was built in 1494 and is an early example of a round-domed mosque. The minaret on the southwestern side was severely damaged by an earthquake in the 18th century.

The Mirahora Mosque complex also included a Quranic school ( Medresa ) and a stone clock tower ( Kulla e sahatit e Korçë s ) , which has long been the symbol of the city. The mosque’s minaret was ceremonially demolished in 1968 by order of the communist regime. After 1990, reconstruction and renovation works began, funded by the Turkish government. The mosque now has a plain white interior. Inside, you can see a series of frescoes depicting Mecca and other important Islamic sites.

6. Birra Korça Brewery

Birra Korça is one of the most famous breweries in Albania. The factory was founded in 1928 by an Italian investor and was the first beer brewed in the country. During World War II, production was stopped; it was then restarted, although the brewery was nationalized during the communist era. The factory then reopened under new management. Today, Korça’s beer factory produces 120,000 hectoliters of beer per year.

Birra Korça is made with natural spring water from nearby Morava Mountain and is light and crisp. The factory also produces a dark pilsner and a dark ale. You can sample the entire range at the Birra Korçë Beer Factory, which also serves as an open-air restaurant and beer garden. It is a half-hour walk from the centre – via Bulevardi Fan Noli. You can walk up behind the tables to see the brewing facilities, take a tour of the brewery and do a beer tasting. Every August, the brewery hosts a five-day Beer Festival.

7. Education Museum in the first Albanian school

In the 19th century, Korça became particularly prosperous. The city developed into a centre of Albanian national consciousness within the Ottoman Empire. Education at that time consisted of Turkish religious education through medresas and universities in Constantinople. The Christian wealthy elite sent their sons to study abroad (such as Thessaloniki and Vienna). It was not until 1887 that the first school education in the Albanian language was established, and in 1891 the first Albanian school for girls followed. The written Albanian alphabet was taught to all students.

This modest stone schoolhouse, now known as the National Museum of Education ( Muzeu Kombëtar i Arsimit ), is dedicated to the history of Albania’s national language. The museum documents the history of the ancient Albanian language and its two alphabets. Displays include documents, manuscripts and archival photographs.

In 1966, in her memoir Illyria Reborn, the writer Dymphna Cusack mentions an encounter with one of the original students of this school:

“I was introduced to a frail old lady dressed in deep black, Efigenia Pendavini, who told me in a soft voice how she had gone to the girls’ school of Sevasti Qiriazi, a remarkable woman who had faced a lot of opposition when she opened the first Albanian school. People used to call us infidels and throw stones at us, but we never gave up. That school worked very hard to develop women. We used to put on plays, with girls playing boys’ parts. I remember especially The Merchant of Venice and Wilhelm Tell. Oh, what a lot of trouble there was with that. The Pasha’s wife said it was subversive!”

8. Bratko Museum of Oriental Art

Curious objects can be seen in the Oriental Art Museum Bratko . It is not really a museum, but a curious private collection. It was opened in July 2003; the dream of Dhimiter Borja (1903-1990), artist, photographer and collector of Asian art and antiques, was realized. Borja was born in Korça, traveled a lot around the world and then spent most of his life in America. In this private museum, 432 objects are exhibited on two floors: Chinese altars, Japanese women’s clothing, Indonesian swords, European medals, Japanese prints, various photographs, which Borja took while working in the Balkans and in Japan as a member of a United Nations delegation. The photographs on display show the social and cultural history of the immediate post-war period and the important role played by General MacArthur in the economic and institutional reconstruction of Japan.

9. The villa districts of Korça

The old villa districts of Korça are located in the eastern part of the city, behind the Orthodox Cathedral. In general, these old houses are well-preserved and it is very nice to walk through these streets and see the different architectural styles of the villas.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the bourgeoisie of Korça really showed its wealth here. These districts form a great contrast with the oldest part of the city, the Penço and Manço districts (the areas above the monument of the National Fighter). In the old part of the city you can see the typical street layout of medieval Balkan centres, with their narrow winding streets and low houses; in the new districts the streets are straight and the houses with walls and gardens are on building plots.

10. Villa Cofiel

I had a great meal in Korça in restaurants at the bazaar, but also in villas in the area behind the cathedral, on Saturday evenings with live music. Villa Cofiel was nice because you could eat well there and the restaurant is beautifully decorated, with old photos and atmospheric lamps. Cofiel serves its own liqueur, raki with cinnamon flavour. I don’t know what fruit it is made of; but it is delicious.…

Experience Korca city tour? Read more about Korca highlights here .